Before it ever enters a digital wallet, bitcoin has a cost. The leading cryptocurrency requires a small country's worth of electricity just to maintain its peer-to-peer network, and the environmental impact of this demand is starting to turn heads.

The Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance estimates that the entire bitcoin network uses 116.7 Terawatt Hours per year, or about half a percent of the world's total electricity consumption. That puts the digital currency roughly in line with the energy use of countries such as Argentina, Malaysia, and Sweden.

The comparison is jarring, given bitcoin's relatively limited role in the world economy, but behind the number is a deeper argument over the very terms of the debate.

Critics of bitcoin's energy use argue that its carbon footprint is way out of proportion with its social value, while supporters assert that bitcoin is no different than the rest of the financial system, which has its own energy needs, and that in the long-run the economic transformation brought on by bitcoin will be worth the investment.

Heavyweights in the crypto space, such as Elon Musk, have weighed in on the debate. The Tesla CEO announced in May, two months after it began taking payment in bitcoin, that his company would no longer accept it due to concerns over the “rapidly increasing use of fossil fuels for bitcoin mining." The announcement was quickly followed by a dip in bitcoin's price.

China has also started cracking down on crypto mining operations, citing concerns over their environmental impact as the country attempts to reign in fossil fuels. The Chinese autonomous region of Inner Mongolia even provided guidelines on how local officials can curb the practice.

As corporations and countries distance themselves from bitcoin's energy costs, some key questions are emerging as flashpoints: What exactly are bitcoin's energy needs? Can they be reduced or made sustainable? And is bitcoin worth the trouble anyway?

Bitcoin's Energy Needs

For many casual crypto-watchers and holders, bitcoin appears as no more than a phantom number rising and falling on a computer screen.

In reality, the cryptocurrency relies on a vast network of powerful computers working tirelessly to validate transactions. The concept, known as proof-of-work in computing jargon, forces participants in the network to solve complex, arbitrary math problems.

These computational puzzles secure the blockchain — the all-important decentralized database that tracks the currency's movements and ensures the authenticity and security of transactions — but they don't get solved on their own.

The people and companies behind this process are called miners, and in exchange for keeping the network running, they're rewarded with a set amount of freshly-minted bitcoin. In theory, it's a virtuous cycle, but it comes with some pesky external costs.

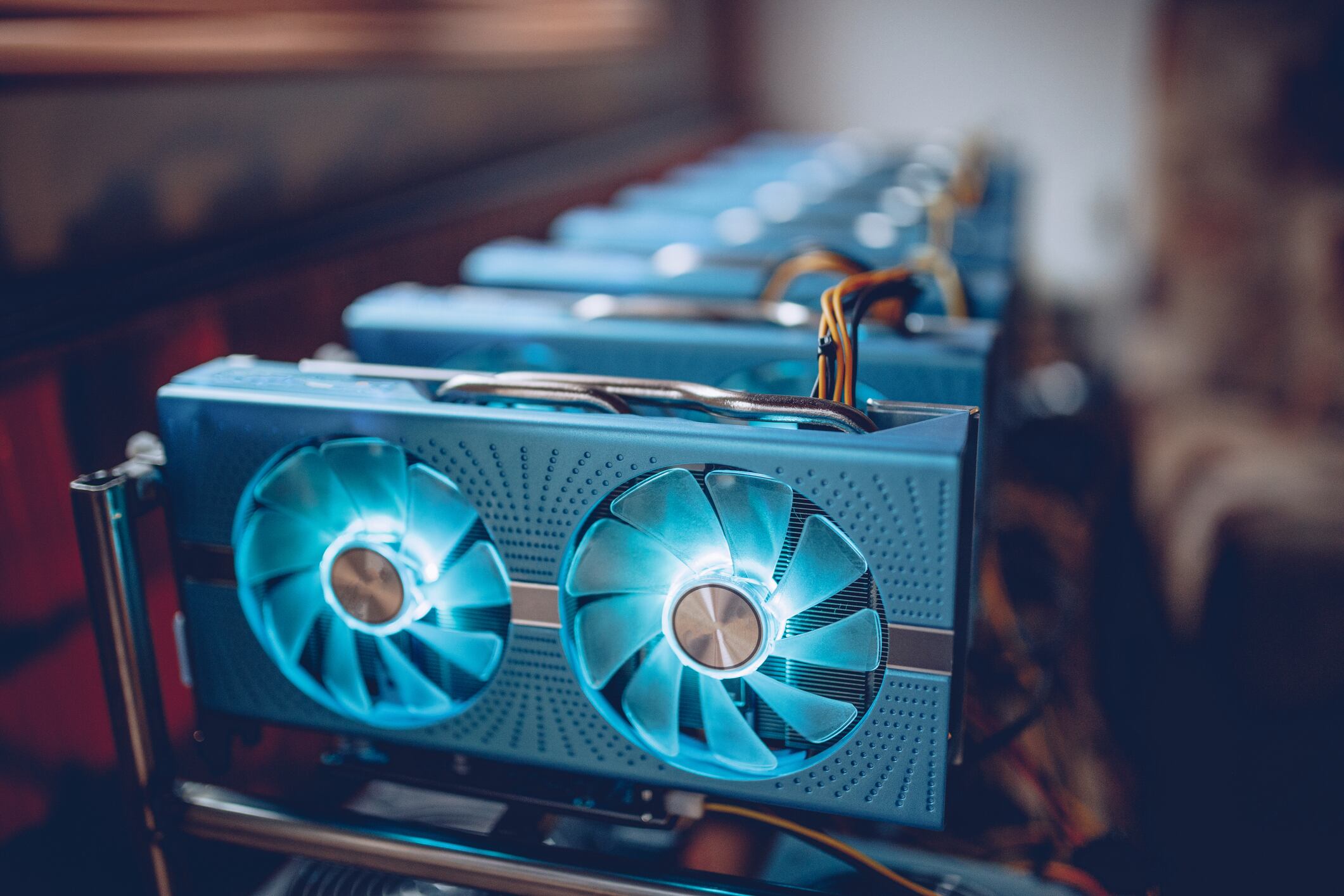

Bitcoin mines are housed in gigantic temperature-controlled warehouses that suck up huge amounts of electrictricity. As bitcoin's price has increased, so has the cost-incentive to mine them, which has meant higher and higher energy needs.

Given that bitcoin does not have the backing of any major banks or settlement platforms, this distributed network is essential. Indeed, the whole purpose of crypto is to avoid institutional middlemen. But is there a way to make it green?

By some accounts, that's already happening. A closer look at bitcoin's energy mix shows that renewables already power a good chunk of mining operations.

A 2020 survey from the Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance found that 39 percent of proof-of-work mining is "powered by renewable energy, primarily hydroelectric energy," with dams in central China providing the lion's share.

Optimistic crypto-enthusiasts say this shift toward renewable energy will continue, but for skeptics that transition won't come soon enough to justify the costs.

Alex de Vries, a digital currency economist who has spoken out against bitcoin's carbon footprint, told Cheddar that the cryptocurrency's current system for minting and validating transactions is fundamentally inefficient.

He described the current system, in which miners compete for a chance to create new blocks of transactions, while only one number wins, as extremely wasteful.

"Everyone is competing with each other to be the first to guess the correct one and take the reward, and there's a whole lot of guesses," he said. "That's why you have millions of machines running 24/7 all around the world using a whole lot of energy."

While the energy make-up of this system could change as bitcoin mints fewer new coins (remember: there are only 21 million in existence) but de Vries pointed out that price increases are likely to make up for any drop-off in mining that come with future halvings — which is when the reward for mining is automatically cut in half every four years.

"From an economic perspective, you have to establish that the amount of energy consumed by this network ultimately relates to the amount of income earned by miners," he said. "If they can earn more, they will employ more machines for the purposes of mining."

In other words, if bitcoin's price stays the same, the amount of energy consumed would necessarily go down as there are fewer bitcoins to mine, but if the price goes up, incentives to keep building out energy-intensive mining operations could continue.

But Is It Worth It?

Nic Carter, a partner at Castle Island Ventures, a venture fund focused on blockchain companies, has been perhaps the most vocal proponent of the opposite perspective: that concerns over bitcoin's energy needs are overblown and often taken out of context.

Across multiple articles, media appearances, and debates, Carter has outlined a fairly consistent argument that tracks with other bitcoin enthusiasts in the industry pushing back against those decrying the cryptocurrency's environmental impact.

One of his main points is that bitcoin will not have the same energy demand going forward, in part due to halving but also because bitcoin will develop its own settlement systems to reduce the number of transactions needing validation on the blockchain.

"One Bitcoin transaction, therefore, can settle thousands of off-chain or near-chain transactions on any of these third-party networks," he wrote for CoinDesk. "Exchanges and custodians could choose to settle up with each other once a day, batching hundreds of thousands of transactions into a single settlement."

He has also stressed that energy demand varies across countries and grids, and total demand might not indicate that bitcoin is driving up energy use on its own. In many cases, as in the use of Chinese hydroelectric power, bitcoin miners are utilizing surplus energy that might have been wasted or curtailed anyway.

Ultimately, however, even Carter admits that coming to terms with bitcoin's environmental impact comes down to whether you think bitcoin is worth the investment (i.e. you believe that a non-state-backed currency is the future of the world economy). In that way, the question is more ideological than it's often given credit for.

"In a sense, arguing over minutiae like the energy mix of bitcoin miners, as I have done in the past, is to miss the point," Carter wrote. "The question ultimately boils down not to the particulars of mining but rather the societal merit of non-state money."