By Wayne Parry

The discovery of four dead women in a drainage ditch just outside Atlantic City was shocking news in 2006.

International media flocked to the seaside gambling resort. More than 100 detectives and prosecutors were assigned to investigate. Casino guests worried about safety, and the victims’ fellow sex workers began carrying hidden knives.

But as the years passed, the public’s attention and fear faded, and the case of the “Eastbound Strangler” – so named for the direction the victims’ heads were facing – remained unsolved.

The arrest earlier this month of a man charged with killing three women whose remains were found on a Long Island beach in 2010 has breathed fresh life into another long-dormant case with obvious parallels; the Gilgo Beach serial killings involve a total of 11 victims, most of whom were young, female sex workers. Yet the recent breakthrough, and the rekindling of public interest, only highlights a painful truth: Many similar cases – like the one in Atlantic City -- remain open.

The FBI would not say how many killings of sex workers in the U.S. remain unsolved. Media accounts and statements from local authorities show a long trail of open cases, from nine women whose bodies were found along highways in Massachusetts, to 11 found dead in New Mexico, and eight more found amid the crawfish farms and swamps of southern Louisiana. The killings of other sex workers in Chicago, New Haven, Connecticut and Ohio, among other places, also remain mysteries.

From the days of London’s Jack The Ripper in the 1880s, serial killers, particularly those preying on sex workers, have often gotten away with it, in part because their victims were easy targets living on the margins of society.

Gary Ridgway, the so-called Green River killer convicted of 49 killings in Washington state, said at during a 2003 court hearing in which he pleaded guilty that he chose sex workers as victims because he knew they would not be missed quickly, if at all.

“I picked prostitutes because I thought I could kill as many of them as I wanted without getting caught,” he said.

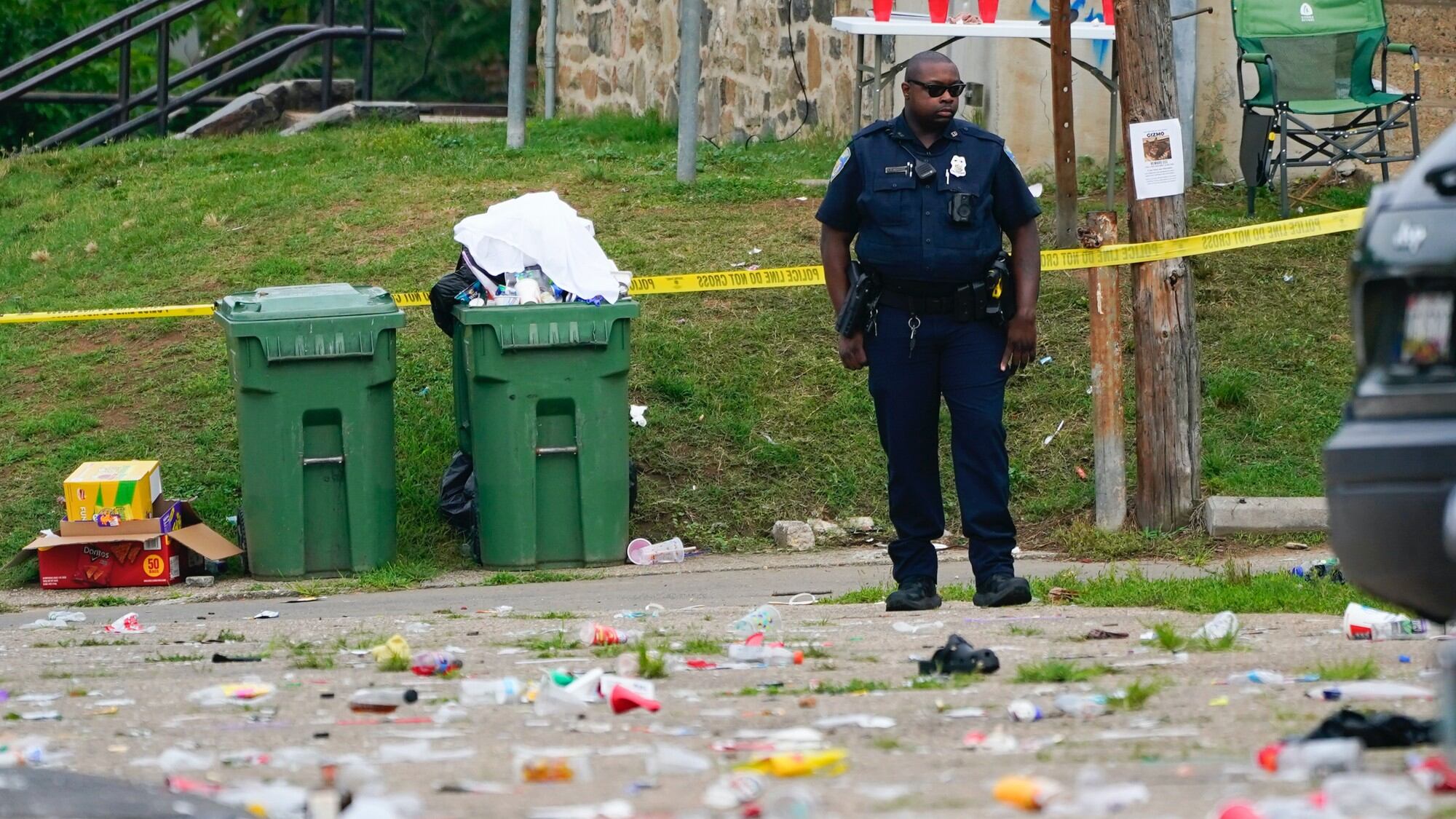

Two women were out for an afternoon walk near Atlantic City in November 2006 when they found a body in a ditch. They called police, who quickly found three others nearby.

The $15-a-night motel in Egg Harbor Township behind which the four bodies were found is long gone. It was torn down in an attempt to clear a seedy area known for crime, drugs and disturbances – and the murders of Barbara Breidor, 42, Molly Jean Dilts, 20, Kim Raffo, 35, and Tracy Ann Roberts, 23.

Because it is near the ocean, like Gilgo Beach, the location has prompted much speculation by amateur detectives about a single killer, but some other online sleuths have pointed out that oceanside areas are often the remotest locations after hours on the densely packed East Coast. Gilgo Beach is about 3.5 hours drive from Atlantic City.

Gone in New Jersey are the four small wooden crosses someone erected on the site, along with the folded-up paper note bearing a Biblical quote promising justice that someone left there on one of the anniversaries of the discovery of the bodies.

For families left behind, each new day without word in the case of their loved one brings fresh pain.

“I kind of lost hope that anyone was even searching for the killer anymore,” said Joyce Roberts, whose daughter Tracy Ann was one of the four Atlantic City-area victims. “The first six months, the prosecutor did get on the phone with me and told me they were working on it.

“Then it just fell off the radar,” she said. “It was like nobody cared anymore.”

That is a sentiment echoed by Phoenix Calida, a former sex worker from Chicago who now advocates for them through the Sex Workers Outreach Project.

“Police departments often refer to it as an ‘NHI’ case: No humans involved,” she said. ”You feel like the only way you’ll be remembered is when they catch the serial killer who killed you, and then they’ll make five movies about him and no one will remember your name.”

Massachusetts State Police are investigating “nine unsolved homicides possibly committed by the same person,” said David Procopio, a spokesperson for the agency. He said two additional missing persons cases may be homicides related to the other nine.

Gilbert Gallegos, a spokesman for the Albuquerque Police Department, said the New Mexico cases remain actively investigated, with “multiple detectives” working them. The 11 victims were all involved in drugs and prostitution, police said.

A reward of $100,000 has been offered for information leading to an arrest and conviction in the case, which involved two victims who were just 15 years old.

Despite the decade-long efforts of a local, state and federal task force, Louisiana has at least eight unsolved apparent homicide cases involving sex workers between the ages of 17 and 30. Their bodies were found in marshy areas in Jennings, a small town in the area known as Cajun Country, between 2005 and 2009.

Prosecutors in New York's Suffolk County investigating the Gilgo Beach cases have been in touch with multiple law enforcement agencies, but District Attorney Ray Tierney would not say which ones.

“Everything is being examined and looked at, and this is an active investigation,” said Anthony Carter, Suffolk County's deputy police commissioner. He would not say if his agency was investigating any connection between Heuermann and the Atlantic City murders.

Atlantic County Prosecutor William Reynolds said the four cases from the drainage ditch outside Atlantic City remain active, with detectives assigned to them, but would not say how many. He declined comment on the Long Island case “as we are not involved.”

Joyce Roberts, the victim’s mother, said no one from law enforcement has called her since the arrest was made in the Long Island cases.

Police in Las Vegas, where Heuermann owns a time share, said they are investigating whether Heuermann may be involved in cases involving the killings of sex workers there.

In the months immediately after the bodies’ discovery near Atlantic City, the local prosecutor’s office and a dozen other law enforcement agencies had 140 people assigned to the cases, Ted Housel, who was prosecutor at the time, said in 2008. By the first anniversary, the total had fallen to 85, and those investigators were also working other cases.

Calida, the former sex worker from Chicago, said women involved the sex trade are frequently robbed by people who know they’re carrying cash, and are sometimes coerced into sexual activity by police in return for not being arrested.

She said an attacker “knows you can’t or won’t report it. You’re an easy target and they know it.”

Three of her friends who were also sex workers in Chicago also turned up dead.

“You see someone, you become friends with them and then one day they’re suddenly just not there,” she said. “We’d all go out asking around and looking for them, and then a few days later a body would be found. There’s always this specific fear that it’s a serial killer. Sometimes we never even get a body back to bury. And we wonder: Will law enforcement take it seriously because it’s ‘just another sex worker?’”

AP writers Susan Montoya Bryan in Albuquerque; Steve LeBlanc in Boston; Julie Walker and Robert Bumsted in Suffolk County, New York; Sara Cline in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and Rhonda Shafner in New York contributed to this story.