When President Bill Clinton was impeached more than 20 years ago, the Senate leaders who controlled his fate say they sought to appear neutral and separate from the White House and wanted to make the trial a bipartisan process.

At least that’s how they remember it today.

“I considered myself a juror and I felt it was important to be as impartial as possible,” then-Minority Tom Daschle (D-S.D.) told Cheddar.

At the time, Republicans controlled both the House and the Senate, while the president was a Democrat. Today’s Congress, grappling with the impeachment of Republican President Donald Trump, is split, with a Democrat-controlled House and Republican-controlled Senate.

It’s not just the two chambers that find themselves divided. The Senate itself is bitterly split down partisan lines, with party leaders speaking to each other through press conferences. Twenty years ago, Daschle and his counterpart in the GOP, Trent Lott, said they spoke to one another daily — and often hourly.

While Daschle said he made it a personal point not to have direct contact with the president or the White House throughout the process, he noted his staff did coordinate with the White House on an “array of issues” that had to be resolved and coordinated.

Lott, the Senate Majority Leader, told Cheddar he and Daschle both wanted the impeachment proceedings to be a bipartisan process.

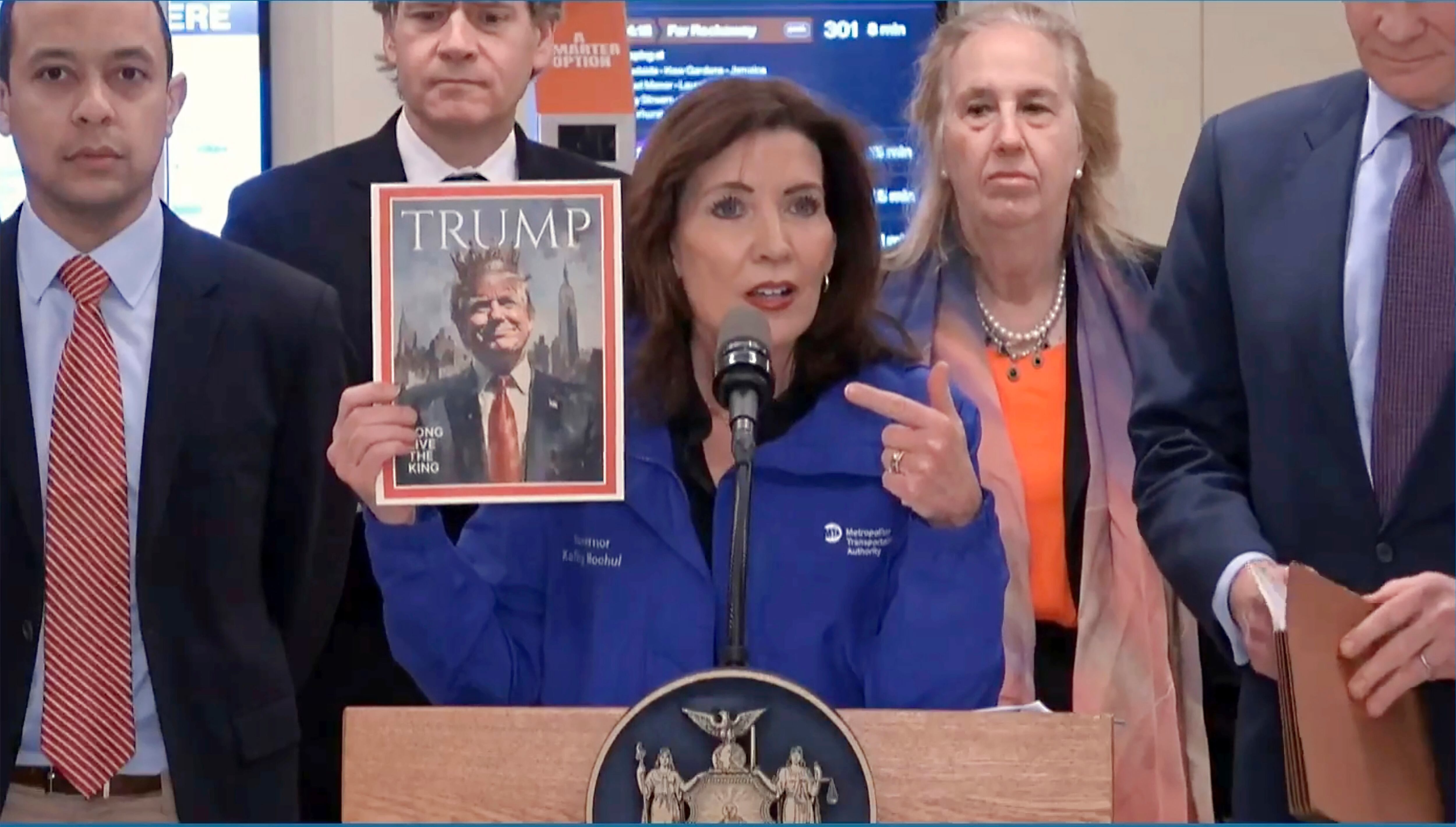

That runs in contrast to the way today's leaders have indicated they will handle the Trump trial. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has said “I am not an impartial juror” and that he intends to coordinate with the White House. “There will be no difference between the president’s position and our position as to how to handle this,” he said.

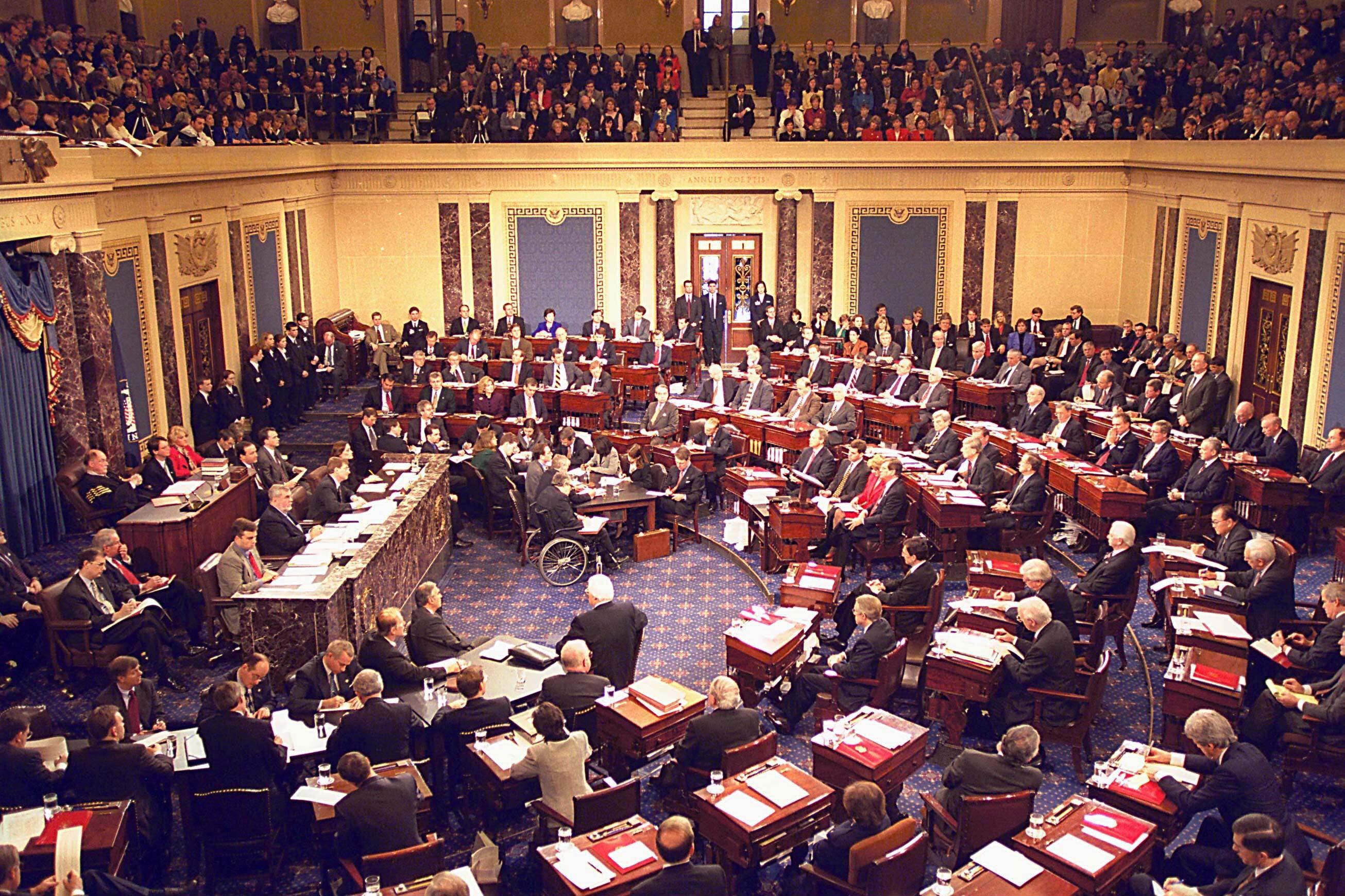

By contrast, in 1999, the Senate voted 100-0 in approving the procedural details of the Clinton impeachment trial, an outcome that would be near miraculous today.

McConnell has told Republicans he plans to move forward with the impeachment trial without committing to interviewing any new witnesses or admitting new evidence. He has also made clear that he has no intention of negotiating with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi on impeachment rules and said the resolution he plans to introduce is “essentially the same, very similar to the 100-nothing vote in the Clinton trial.”

The de-facto set of rules McConnell said he intends to follow are those established by Daschle and Lott in the Clinton impeachment, which set rules for how the Senate trial would start and delayed consideration for new witnesses or evidence until after opening arguments and questions by Senators.

The Senate trial will begin with presentations from House-selected managers, followed by the president’s lawyers setting up his defense. After both sides have given their respective arguments, Senators are able to ask questions in writing to the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, who presides over the trial. After that, the Senate majority and minority leaders may decide whether to vote on further questions.

During Clinton’s impeachment trial, House managers later forced a vote to call witnesses to testify on the Senate floor, which failed 70-30. Instead, the Senate decided to question three witnesses (including Monica Lewinsky) behind closed doors and allow Senators to read the transcripts.

Today, unlike in 1999, there is still a dispute at the trial’s outset about material witnesses that have not yet been heard. Democrats are calling for new witnesses and new evidence to be presented during the Senate trial, particularly after former White House National Security Adviser John Bolton announced, after months of back and forth, that he will testify if subpoenaed and after Democrats released documents obtained from Lev Parnas, a close associate of the president’s personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani who was implicated in the Ukraine scandal. Trump has directed key witnesses to not testify and has withheld documentary evidence.

In Clinton’s trial, every major witness had already testified before the trial. Senator Mitt Romney has said “going with the Clinton impeachment process is satisfactory to me because that process did provide, down the road, for an opportunity to hear from witnesses.”

Now, the trial of the president will move forward before Senators can agree on a bipartisan plan for proceeding. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi had held onto the impeachment articles for weeks amid the dispute, but ultimately sent them over on Wednesday.

Lott said of the current Senate, “When they get through the first phase, they can decide what they want to do.”

It takes 67 senators to remove the president from office, but only a majority to rule on the procedural issues surrounding the trial. Republicans currently hold 53 seats in the Senate. In the current political climate, it is a virtual certainty that Democrats will not get enough votes to remove President Trump.

But to determine the rules the Senate will employ, only four Senators would need to defect, and there are signs that at least four might be open to calling new witnesses.

Bipartisan ‘Partnership’ Based on ‘Trust’

The eventual Trump trial, much like the Clinton trial, promises to be a political spectacle. The two party leaders, McConnell and Democrat Chuck Schumer don’t seem eager to speak to each other about the trial.

When faced with the same challenge of holding an impeachment trial, Lott and Daschle took a different approach. “The moment the House voted some 21 years ago to impeach President Clinton,” Lott said he called Daschle and essentially said, “Whether or not we like it, this thing is in our lap and we’re going to have to do our constitutional duty, so I hope we can stay in touch and talk to each other rather than talk to the media.”

“[Daschle] seemed to appreciate the call,” he added.

The Senators had phones on their respective desks with direct lines to one another and Daschle said the two became close professionally and personally. He called it a “partnership I trusted and a partnership I valued and one I look back on with enormous gratitude.”

Lott went ahead with the Senate trial despite criticism that Republicans did not have enough votes to convict a president and remove him from office, but that wasn’t the only sign of trouble at the start.

Once the Senate knew the articles would be sent from the House, Senators tried and failed to get an initial set of rules on paper. Lott and Daschle liked the initial proposal, but House managers did not. Chief Justice William Rehnquist recessed the trial because there were no rules in place.

After that, the 100 senators convened in a closed caucus to successfully talk it out.

“Somebody came up with the idea we would have the Senate — no press, no staff — meet in the Old Senate Chamber and talk about how to proceed,” said Lott.

Before the full Senate began debate, Lott said he asked his Democratic colleague Robert Byrd, the longest serving Senator in U.S. history, to give a tutorial on what the U.S. Constitution required on the impeachment. Lott also asked the Democratic senator from Alaska, Daniel Akaka, to lead a prayer before beginning the meeting, which was held in the storied room.

“There’s an aura in the Old Chamber that you can’t even really articulate,” Daschle said.

After the conclusion of the trial, Rehnquist had said he was “impressed” by how Lott and Daschle had worked together on procedural rules in spite of their political differences.

Daschle called it “lamentable” that today’s Congressional leaders have not yet been able to “recreate that degree of bipartisanship.”

“There are important constitutional responsibilities and I think it’s critical that the institution itself be paramount in the decision-making and in the relationship that is required from the leaders and from the two caucuses,” he said.

In the Old Senate Chamber 21 years ago, “long story short, we were getting along,” Lott said.

1999 Rules: Template or Precedent?

Then, like today, the House voted to impeach the president days before Congress left for recess. Clinton was impeached on December 19, 1998 and Trump was impeached on December 18, 2019. The Senate took up the Clinton charges in January 1999.

“We didn’t know right out the gate how we were going to proceed,” Lott said. “We didn’t go immediately to taking up articles of impeachment. We were back in session in January for several days before we moved to take it up.”

“One of the reasons we were able to go forward the way we did is because I had such a strong relationship with Tom Daschle,” Lott said. “I trusted him, I respected him and he knew I would keep him posted and updated regularly throughout the process but not through the press. The leadership [today] is different.”

Lott and Daschle wrote an opinion article together in October 2019 imploring today’s Congress to “put aside those differences and conduct a fair, nonpartisan presidential impeachment trial.”

During the Clinton-era, the leaders worked closely on creating a set of rules both caucuses were in favor of supporting. “Each impeachment is so different,” Daschle said. “The circumstances are different.” But, he added precedent is not so “imperative that you can’t consider alternatives.”

“We laid a template on how to proceed,” Lott said. He said it was generally thought to be “fair and civil.”

Now Daschle worries “people’s confidence in the process and in the institutions themselves are at stake. This isn’t about parties, it ought to be about institutions and the constitution and I hope that can be reflected as time goes on.”