Semiconductors are the tiny workhorses behind every laptop, phone, and automobile. Most commonly made with silicon, these tiny chips control the flow of electricity through devices and serve as the backbone of high-tech manufacturing from San Francisco to Shenzhen.

Lately, though, companies are struggling to get their hands on these precious bits of crystalized silicon. Suppliers across the world cut production early in the coronavirus pandemic due to expectations of slower near-term growth, and now demand is far outpacing supply, leaving manufacturers and whole industries in a lurch amid an already fragile economic recovery.

Given how complex the semiconductor manufacturing process is, ramping up production again won't be easy, and some expect the shortage to last for at least another six months.

In the meantime, national leaders are doing some soul-searching when it comes to chips. President Joe Biden, for instance, last week ordered a 100-day review of the U.S. semiconductor industry, with the goal of identifying gaps in the domestic supply chain. He also called for $37 billion in federal funding to bolster the sector here in the states.

"We need to make sure these supply chains are secure and reliable," Biden said at the signing. "I'm directing senior officials in my administration to work with industrial leaders to identify solutions to this semiconductor shortfall and work very hard with the House and Senate."

According to the Semiconductor Industry Association, America's share of the global industry has fallen from 37 percent in 1990 to 12 percent today. While many U.S. industry leaders and politicians have long encouraged and actively facilitated globalization, coronavirus has created a new awareness of the vulnerabilities that can come with a world-spanning supply chain.

For semiconductors specifically, which are essential in sensitive industries such as defense, automobiles, and communications, this could mean a sea change in how countries manage their domestic industries. To better understand this shifting perspective, Cheddar assembled a timeline of the semiconductor shortage stretching back to the misty pre-Covid economy.

Before COVID

Long before coronavirus threw the global economy for a loop, a simmering U.S.-China trade war had already disrupted the sensitive semiconductor supply chain.

In July of 2018, the Trump administration imposed 25 percent tariffs on imports of Chinese semiconductors, alleging that the country was engaging in unfair trade practices.

In 2019, the administration followed that move with export controls targeting the global semiconductor supply chain. Specifically, it restricted Chinese tech giant Huawei from buying chips from Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC), the largest supplier of semiconductors by market cap, making up roughly a third of the global market.

In the lead-up to the ban, Huawei started stockpiling semiconductors, which put additional strain on TSMC and pushed other clients, such as automakers, to the back of the line.

China's own largest chipmaker, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), lacks the same technological prowess of TSMC or South Korea's Samsung and has struggled to keep up with demand. On top of these internal shortcomings, the Trump administration banned U.S. companies from exporting crucial technology products to the company. In response, China banned American firms from importing chips from SMIC.

So far, these bans have survived the transition to a new administration, as Biden has yet to make a firm pivot away from Trump's aggressive stance toward China.

All of this has set the stage for the shortage, but it was COVID most of all that tipped the scales toward a widespread disruption.

Electronics Boom to Automotive Bust

Like most manufacturers, chip-makers were impacted early on by the coronavirus pandemic, as they moved to protect their workers and prepared for shifts in global demand.

This disruption was short-lived, however, as orders started pouring in from electronics companies, which saw significant demand for devices even at the peak of the pandemic.

Many commentators have pointed to increased work-from-home, homeschooling, and more interest in home entertainment such as streaming and gaming as the reason for the spike.

Indeed, Sony blamed the chip shortage on why it couldn't meet the demand for PS5s.

The consumer electronics market generated a record $442 billion in sales revenue in 2020, up 5.5 percent from the year prior, according to the Consumer Technology Association. The group noted that demand for computers, smart home devices, and entertainment systems — all products packed with both high-end and low-end semiconductors — powered the uptick.

In light of this, electronics firms have avoided the worst impacts of the shortage. For automakers, it's been a different story, in part because just-in-time manufacturing has long dominated the industry. Many firms significantly cut their chip orders early in the pandemic, and then when demand returned quicker than expected, they were at the back of the line.

As a result, automakers, which use semiconductors in components such as power steering and electronic consoles, have cut production in line with the shortage.

In January and February, Ford, General Motors, Nissan, Toyota, Stellantis, and Volkswagen were among the companies to announce cuts.

AlixPartners, a consulting firm, predicts that the shortage will cost the industry a whopping $60.6 billion in revenue within the year.

Similar semiconductor woes are impacting Chinese tech giant Huawei, which recently told Cheddar that it would not be getting into the electric vehicle market. The company also notified its suppliers that its smartphone component orders, a crucial aspect of its business, would fall by more than 60 percent in 2021, according to a report from Nikkei Asia, due to U.S. trade pressures and the chip shortage.

On the supply side, meanwhile, the U.S. chip-making industry is kicking into high gear. Nvidia acquired British chip designer Arm in a deal topping $40 billion, while Advanced Micro Devices has announced its plan to acquire Xilinx, a provider of adaptive computing solutions, for $35 billion.

Biden's Response

Industry players haven't been shy about asking the federal government for support. Medical device makers and manufacturers sent a letter in February asking the Biden administration to fund a program created in 2020 to provide subsidies for chip research and factory construction. They also requested a new investment tax credit to draw money to domestic projects.

Biden's call for $37 billion in funding for the industry is a response to these requests, but lawmakers still need to pass a funding bill.

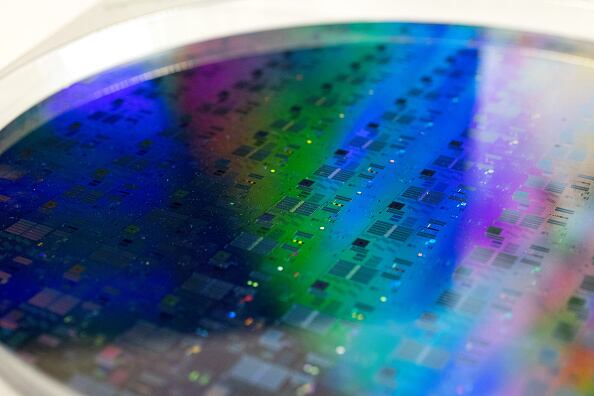

In addition, a bipartisan group of eight governors from states with significant auto industries are calling on semiconductor plants to expand their production and "temporarily reallocate a modest portion of their current production to auto-grade wafer production." (A wafer is the thin slice of semiconductor material like silicon used to build chips and solar cells.)

The group is also calling on Biden to do more in putting pressure on the industry, in particular by "continuing the drumbeat on behalf of automakers in the U.S. and their workers until there is a sufficient semiconductor supply to meet the strong demand for our vehicles, which has been one of the bright spots in our recovering economy."