By Rebecca Santana

Ammar Rashed has a stack of letters from U.S. troops attesting to his work during some of the most dangerous days of the Iraq War. But six years after he applied to immigrate to the United States under a program for interpreters who helped America, he is still waiting.

“You don’t have to keep me and my family suffering for, for years waiting,” said Rashed during a Skype interview from Jordan, where he lives. “It’s really frustrating.”

Rashed is among thousands of Iraqis, many of whom risked their lives by working closely with Americans during the war and its aftermath, trying to enter the U.S. An estimated 164,000 Iraqis already have found homes in America.

U.S. officials cite multiple reasons for the delays, including an attack on the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad, a hack of a refugee database, the COVID-19 pandemic and cuts to the refugee program under then-President Donald Trump.

Sometimes the process is slowed as applicants struggle to prove their ties to the U.S.

Mohammed Subhi Hashim al-Shafeay, his wife and four children have been in limbo for a dozen years while he tries to document his work for a U.S. security contractor at the Iraqi Justice Ministry.

They are living as refugees in Jordan. But al-Shafeay cannot work and cannot afford to send his oldest child, a high school senior, to college. His youngest children feel resented at school because Iraqi refugees this year were exempt from paying school fees, unlike low-income Jordanians.

“This is not a life. We want a future for our children,” he said.

The U.S. invasion in 2003 unleashed a vicious sectarian war that engulfed Iraq. Then militants seized large swaths of territory. Iraqi forces reclaimed their country in intense fighting, but huge challenges remain, including rampant corruption, a lack of basic services, continued violence and more than 1 million people still internally displaced. Between the invasion and this year, as many as 300,000 Iraqis were killed along with more than 8,000 U.S. military, contractors and civilians.

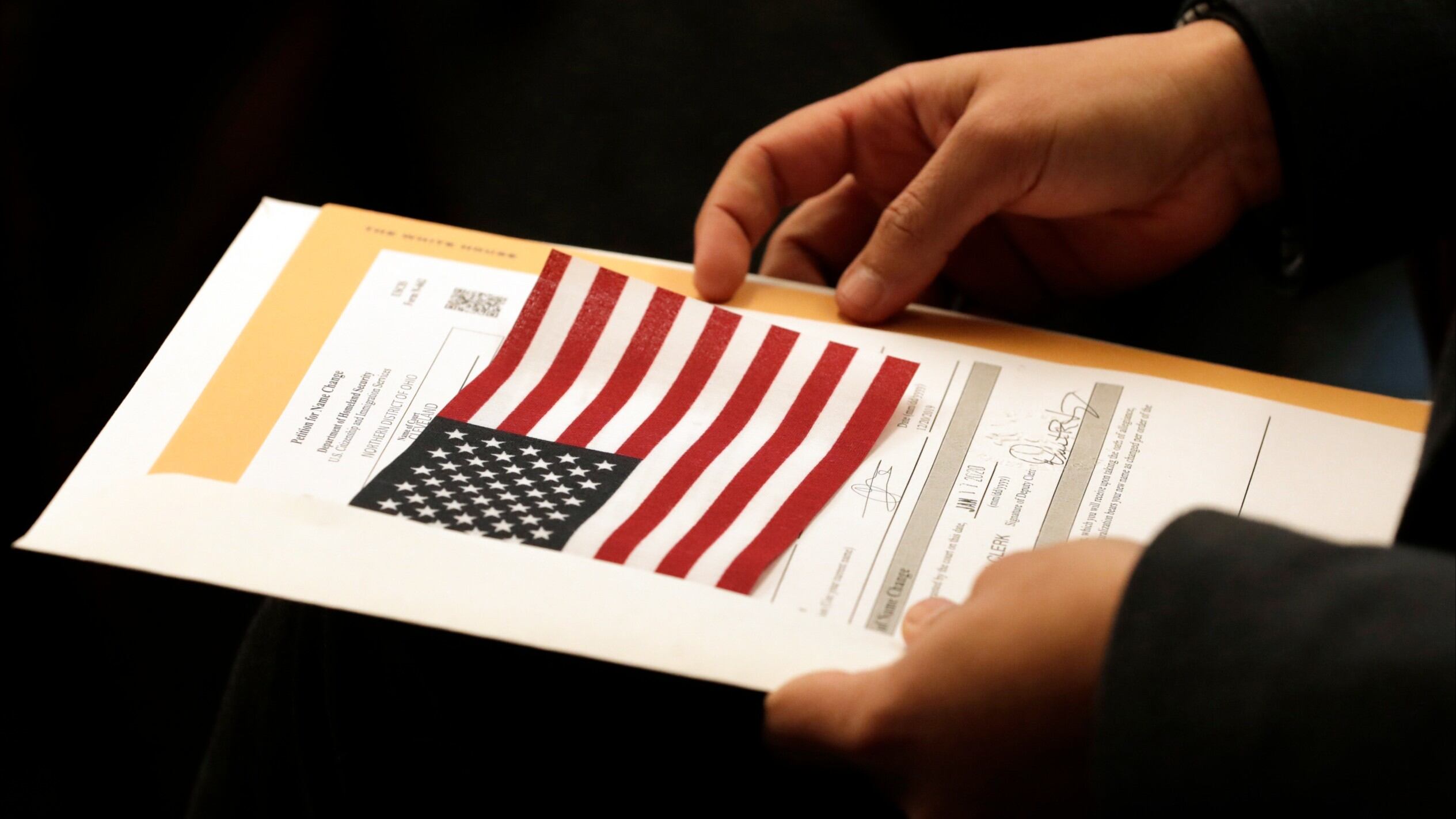

Recognizing the role Iraqis played in helping the U.S., as well as the violence they faced for it, the U.S. established ways to help them emigrate.

According to the State Department, 106,000 have applied for a program, known as direct access program, intended for people affiliated with the U.S. such as those who worked for an American nongovernmental organization. There are also about 100 Iraqis who applied for a more narrow special immigrant visa program for Iraqis who worked directly for or on behalf of the U.S. government. That program stopped accepting applications in 2014, but applications already in the pipeline are still being processed.

Rashed applied under yet another route, which allows for 50 visas a year for interpreters who have a recommendation from a general.

Almost since the beginning there have been complaints the process to come to America takes too long. Multiple administrations have considered making the programs more efficient without compromising security.

The State Department declined requests for an interview for this story. But in reports, U.S. officials noted steps such as added staff to speed up visa processing. The embassy in Iraq's capital just reopened limited consular services last fall after closing for three years following a 2019 attack. The government also noted the toll that the pandemic took on its visa processing around the world and the shifting of federal resources to the crisis in Ukraine. The U.S. refugee program, which endured historic cuts under Trump, only in recent months has started to show signs of recovery.

In January 2021, the U.S. suspended the direct access program after three people were charged with stealing information from a U.S. refugee database to fraudulently help Iraqis trying to emigrate. The program was not restarted until March of last year. At the time it reopened, the U.S. said it was “committed to ensuring those who sacrificed their own safety for our collective interests have an opportunity to seek refuge in the United States.”

For the Iraqis still waiting, it can be confusing.

Al-Shafeay said he was hired by a U.S. contractor to work as a bodyguard for the Iraqi Justice Ministry from 2003 to 2006, when he left Iraq. He said he has been told the holdup is confirming his employment, but it is challenging so many years later and from afar.

He and his wife are worried about their children. Jordan has played host to tens of thousands of Iraqi refugees over the years, but those refugees face challenges getting authorization to work, especially in major professions, and are essentially barred from becoming citizens. Al-Shafeay questions what future his family has there. The family relies on handouts from aid groups.

Al-Shafeay said the family is scared to ever go back to Iraq because a former in-law, who is now a member of an Iranian-backed militia, has repeatedly threatened them. His oldest child is a high school senior but barely leaves his room. He says there is no point in studying because his parents cannot afford the university fees in Jordan.

Ali Al Mshakheel is a former Iraqi journalist now living in Maine. He said he hears almost daily from Iraqis in America trying to assist family or friends still in Iraq. Al Mshakheel himself has four siblings and a father whom he has been trying to help emigrate. During the program's suspension, he wrote an op-ed calling on the Biden administration to unfreeze it. Even now he sees little progress.

Both Rashed and al-Shafeay still want to come to the U.S.

Rashed spent most of his life in Iraq. Now, it is too dangerous for him there due to the work he did for the American military. He said he worked with U.S. troops in 2008 who were fighting the Mahdi Army — supporters of Muqtada al-Sadr. But now, as al-Sadr has become an important political figure, his supporters are increasingly in positions of power. Rashed is both a Jordanian and Iraqi citizen, but he does not see a future for his children in Jordan.

“I need them to live better with a better nation and a better future,” he said.

The people working to help him are frustrated, too. Rashed’s lawyer, Wes Pickard, said Rashed completed his consular interview in 2019. At that time, there was a reasonable expectation that the process to get his visa would move quickly after that.

Since then Rashed's been stuck in what’s called “refused for administrative processing” — background checks — with little indication as to when the process will be finished.

Jennifer Patota, a lawyer for the International Refugee Assistance Project, said there are a number of reasons why people could be stuck in background checks — their name is similar to someone else’s that the government has suspicions over, for example.

Kevin Brown worked with Rashed over two tours in Iraq and wrote him a letter of recommendation. Now retired from the military and living in Connecticut, Brown said it is frustrating to hear that someone he worked with so closely — “his right hand man” — is still waiting.

Brown said he would love for Rashed to become an American citizen "But if he can’t be, I’d like to know why.”

Associated Press reporters Karin Laub and Omar Akour in Amman, Jordan, and Qassim Abdul-Zahra in Baghdad contributed to this report.