On Wednesday morning, a crane lifted Philadelphia's most controversial public statue from the steps of the Municipal Services Building near City Hall. While plans to move the statue were years in the making, the surprise uprooting came amid the most heated protests in the city's recent history, when angry demonstrators attempted to burn and tear down the 10-foot-tall bronze monument.

"We just needed to get it out of the way so we can move forward," said Mayor Jim Kenney later that day. "If there's someone who wants it, wants to take it somewhere else, we'll talk. We needed to get it to a place where it was out of people's sight."

Who was the man behind the statue who inspired such anger? A Confederate general? A fallen dictator? The answer is none of the above, but instead Philly's own special kind of boogeyman.

You might have heard of Frank Rizzo. The police chief-turned-mayor of Philadelphia was the city's best known and most divisive public figure through much of the 1960s and 70s. He was that rare big-city mayor who made a name for himself nationally, in no small part due to his outsized personality and colorful, often offensive, use of his native South Philly tongue.

As a top police official, he presided over a campaign of harassment of gay and black citizens, raided the offices of civil rights protestors, and used violent tactics to disperse protests. As mayor, Rizzo further empowered the police, hobbled public housing projects, and traded in flagrant racialized language that might have made Richard Nixon blush in order to appeal to the white, working-class voters who were his loyal base.

While his supporters saw him as a champion of working-class neighborhoods, his legacy has largely been one of loathing from residents who want to see the city become more equitable.

Wilson Goode, later the first black mayor of Philadelphia, once called him "the first coming of Donald Trump," a comparison that more than a few others have made in recent years, drawing a line between their populism, race-baiting, and off-the-cuff manner.

But Rizzo's controversial legacy isn't the only reason we're still talking about him. His 3,000-pound statue has itself inspired years of debate over whose likeness should be propped up in the public square. For the many Philadelphians who still saw Rizzo as a symbol of racism and oppression, it was a daily slap in the face.

"We knew about his history as police chief and mayor, and we knew about his statue in front of the Municipal Services Building, and we felt that was inconsistent," said Deandra Jefferson, an organizer for Philly Real Justice, a local prison abolition group.

The group launched the campaign to take down the Rizzo statue in 2017, around the same time that activists across the South were calling for the removal of century-old Confederate statues.

"Frank Rizzo is inflammatory enough and his legacy is oppressive enough to equal the oppression of a Confederate statue in the South," said Jefferson, a Philadelphia native.

Councilmember Helen Gym, whose office overlooks the courtyard where the bronze Rizzo once stood, was among the first public officials to get behind the effort. She said the murder of a protestor in Charlottesville, Virginia in August of that year by a neo-Nazi and white supremacist spurred her commitment.

"On City Council, I made it very clear that we would miss the point in Philadelphia if we thought Charlottesville was about the Confederacy and the South," she said. "We had our own sins to confront. The Rizzo statue was as much a symbol of Philadelphia's troubling past with racist and violent policing."

The protests have spurred other removals as well. Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam announced Thursday that the statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee would be removed as soon as possible from Richmond's famous Monument Avenue.

Tying Rizzo with the broader movement to topple Confederate statues, however, had its complications. One being that much of the mayor's old constituency is alive and well in Philadelphia.

"In both cases, there are contested memories," said Timothy J. Lombardo, author of Blue-Collar Conservatism: Frank Rizzo's Philadelphia and Populist Politics. "There are plenty of people throughout the South who will argue up and down that the Confederacy had nothing to do with slavery, despite all historical evidence to the contrary. That's a little more complicated when it comes to Rizzo because there are still people around who still remember him personally."

Indeed, personal connections with Rizzo abound in Philadelphia's governing establishment, not to mention deep roots in South Philadelphia, where Rizzo grew up. A mural of the former mayor in the city's Italian Market is beloved by many, even as it is routinely splattered with paint and graffiti.

(In line with the statue's removal, the Philadelphia Mural Arts organization said it was cutting all ties with the mural, effectively leaving it to fall into disrepair, which could happen sooner rather than later if vandals swoop in to finish the job.)

Prior to the protests that have broken out following the death of George Floyd, Mayor Kenney, a South Philly native himself, already publicly supported the idea of moving the statue, but his plan was to align the removal with a 2021 renovation of the surrounding plaza.

This week, this week, the mayor said that was a mistake. "We prioritized efficiency over full recognition of what this statue represented to black Philadelphians and members of other marginalized communities."

Activists attribute the delay to the difficult politics of opposing Rizzo even three decades after his death — which happened, by the way, in the middle of a third run for mayor, this time as a radio shock jock-turned-law-and-order Republican.

"What happened is [Kenney] dragged his foot, and the people said we're going to take it down one way or another," said Jefferson. "There was an easy way to prevent things like that, and it was listening to people before it got to this point."

Another reason for moving the statue now was the risk of angry protesters actually succeeding in tearing it down.

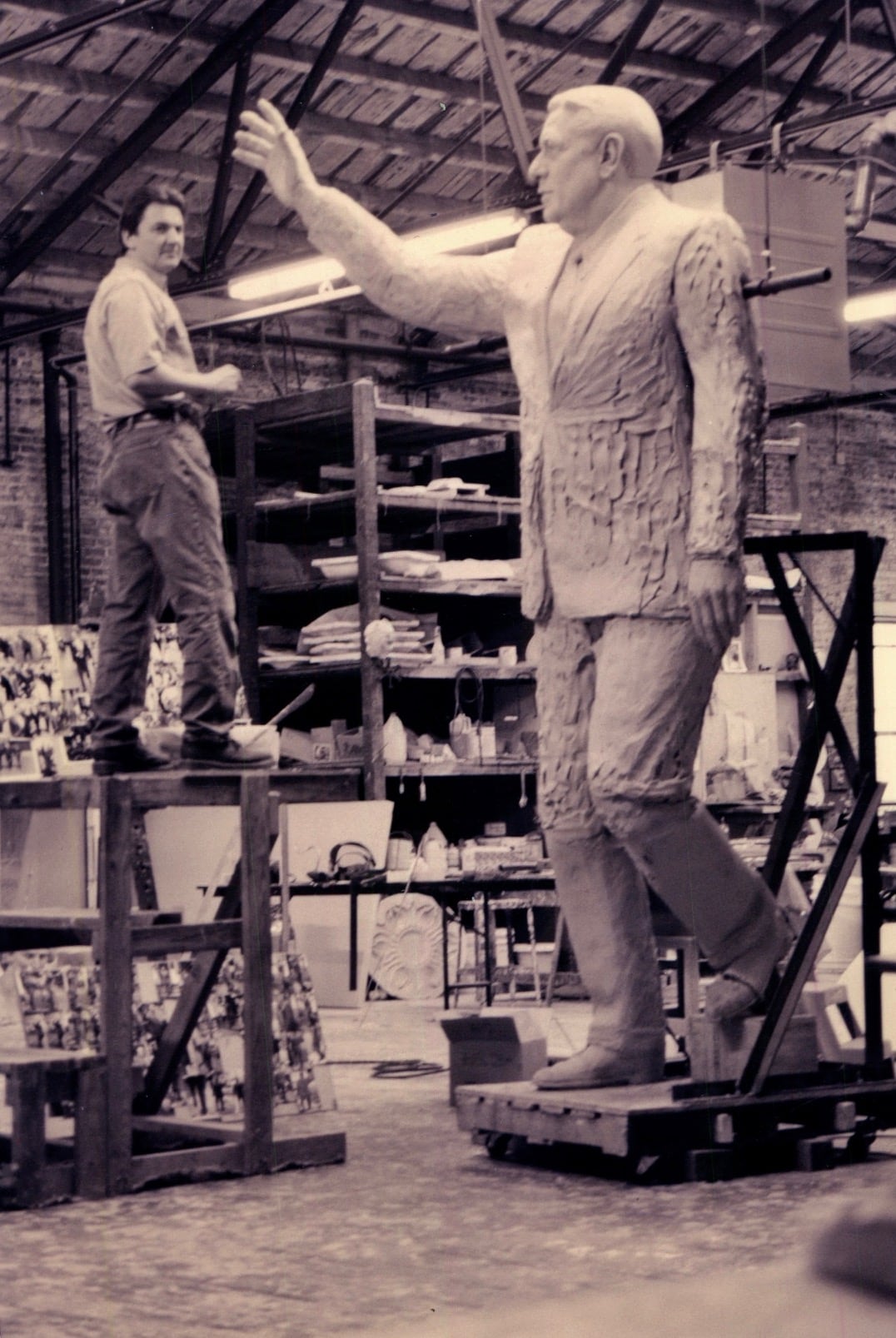

"I have some mixed feelings, because I sculpted it, but generally I felt a great sense of relief that it was removed in the middle of the night when no one was around," said Zenos Frudakis, the artist who sculpted the giant-sized Rizzo, which was erected in 1998. "I was very concerned that the violent dislodging of the statue would harm someone."

In the past, Frudakis pushed back against calls to remove the statue, arguing for the more "subtle" approach of contextualizing it with other monuments or educational plaques. That began to change when he saw how determined people were to tear it down.

"I could see that it's kind of gotten to the point where there's not going to be a subtle, nuanced, contextual response here, like adding other sculptures or making it didactic," he said. "It was to the point where you're hitting a sculpture over the head with a hammer. A hammer is not subtle."

But this is hardly the first time Rizzo's statue was targeted. Over the years, it's been vandalized, spray-painted, and even, on one occasion, wrapped in a massive, pink knitted bra. The fact that the latest protests finally toppled him was a surprise to many.

"I want to emphasize that no one should take lightly this idea that even symbolic testaments to racism and oppression can be easily moved and changed," said Councilmember Gym. "It took thousands of people over years who put in blood, sweat and tears and made it impossible for the city to ignore our voices."

The physical act of ripping the statue out of the concrete, however, was a quick and relatively simple process.

"At the end of the day, the removal of the Rizzo statue was not difficult," said Gym. "It happened in a matter of hours. It did not require a massive amount of money to redesign Thomas Paine Plaza. It didn't require an Art Commission stamp of approval. It required people to say you cannot say no to us."