For the cruise ship industry, it has certainly been a trying time with ships docked throughout the coronavirus pandemic.

The industry was one of the most visibly hit during the onset of COVID-19, with headlines about passengers and employees sick and trapped at sea. The shutdowns were swift, and getting the giant vessels back in circulation has been slow. There are concerns about the future of the industry even with phased relaunch dates in sight, and some cruise lines are turning to recycling as a means to stay afloat.

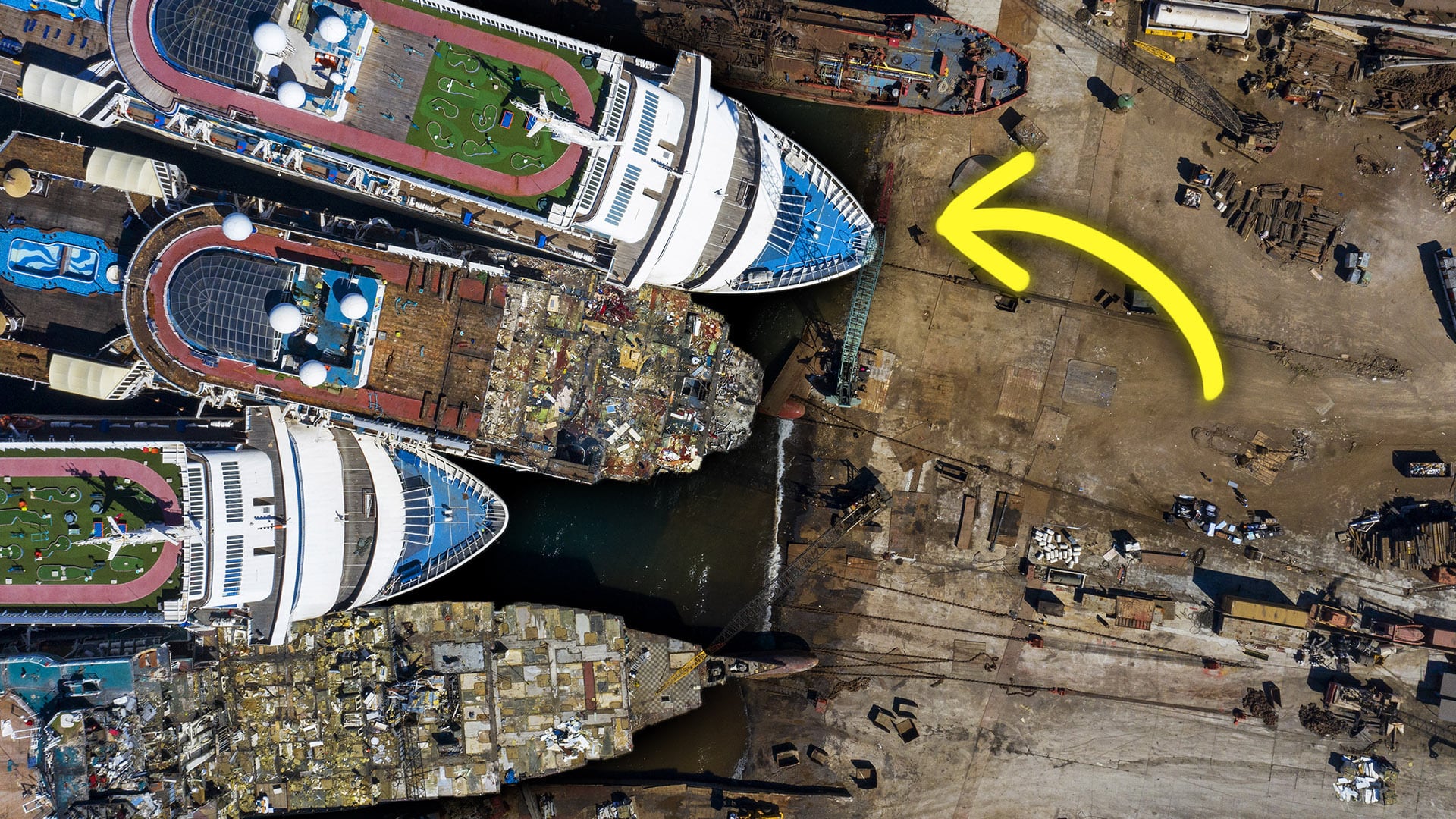

Ship recycling or shipbreaking is a common practice where an aged vessel is broken down so its component materials can be repurposed. With cruises largely non-operational, the rate at which cruise lines have been selling decommissioned vessels to shipyards around the world has ticked up.

On average, 70 to 80 percent of the world's decommissioned ships are sent to graveyards, as they're called, in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. Typically, most vessels that end up there are oil tankers, cargo ships, and containers. Ship graveyards in these regions often offer more money for the ships than other global locations.

"South Asian yards are now able to offer shipping companies around $450 per ton. Turkish yards offer around $250, European yards around $150. And these demolition rates depend mainly on the domestic steel market, on labor costs, and environmental measures that are followed and implemented at the yards," Nicola Mulinaris, communication and policy officer at NGO Shipbreaking Platform, told Cheddar.

Cruise Companies Opt for Turkish Yards

While South Asian ship graveyards typically offer the most bang for your buck, the beaching method used in these yards is controversial because of the impact on the environment. In these locations, a ship is taken to a tidal mudflat where it is grounded during high tide. This method presents an opportunity for hazardous materials to leak into the water.

However, the operation in Aliaga, Turkey, is seen as more environmentally sound.

"In Turkey, the landing method applies. The bow or front of the vessel is grounded on the shore while the stern is still afloat, and the blocks are lifted by cranes onto a drained and impermeable working area," Mulinaris noted.

Once the vessels have been broken down, the steel and metal pieces are sold for construction or automobile production.

"Almost every part of the ship can be reused and recycled. A ship is mainly made out of steel, so roughly 90 percent of a ship is steel, which is basically recycled and reprocessed. Then there's machinery that can be resold," Mulinaris said, also noting that the furniture can be a boon for scrappers.

Multibillion-Dollar Losses

Last year, the Aliaga ship recycling facility in Turkey began taking on a new type of ship — cruise liners — as companies tried to cut costs and recover some of their losses. According to the industry, the pandemic and the subsequent CDC no-sail order led to a global loss of $50 billion in economic activity just between March and September.

The Carnival Corporation alone noted a loss of $10.2 billion in 2020 and sold 19 ships. At least six of them went to scrappers.

Large companies typically retire cruise ships after two to three decades, but those ships are usually extended a lifeline when they're sold to smaller cruise lines that refurbish and reuse them.

As vaccination efforts ramp up in the U.S. there is growing optimism that American ports could be bidding bon voyage to travelers sooner than later. Carnival sent two cruise ships to Galveston, Texas just this week after more than a year, a sign that it's standing ready to set sail when the time comes.

Video produced by Christine Beldon and Sarah Kate Gervasoni. Article written by Lawrence Banton.